It turned out that Phil Smith, Uncle Jack’s old pilot, lived with his wife, Mollie, in an old house perched on the side of a steep hill in the well-to-do North Shore suburb of Mosman. After exchanging letters for several months, my entire family – Mum, Dad, two sisters and me – found ourselves walking, slightly nervously in my case, up a short steep driveway that led past a carport to a set of steps up to the front porch. Though a few months off 80 years of age, the man who opened the door when we knocked was a surprisingly sprightly-looking chap.

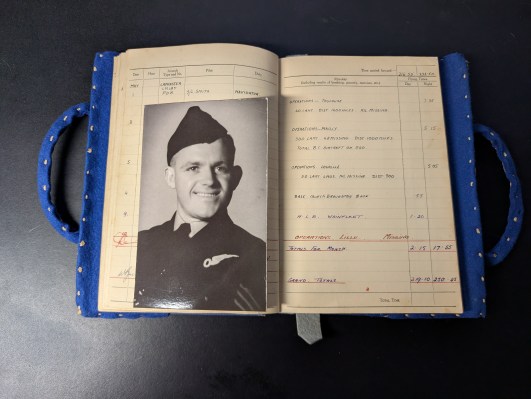

Over the next couple of hours, and over a dining table groaning with breads, cheeses, salad and cut meats, we slowly got to know this remarkable but modest old fellow. He was a reserved sort of chap, quietly-spoken but with an unmistakable air of authority about him. He played down his experiences, telling us that he wasn’t sure how much he could help because he couldn’t directly remember our Uncle Jack. He couldn’t, or wouldn’t, tell us much about what happened on that final flight. The only tales I distinctly remember him telling us was a rather astonishing one about his troop ship hitting an iceberg mid-Atlantic on the way to England, and how he once, after the war, walked accidentally and unsupported all the way to the top of Mount Fuji in Japan. But Mollie persuaded him to retrieve a small wooden box from a drawer that was otherwise chock-full of papers and documents. Inside was the coloured ribbons and medals awarded for his service, including the polished silver decoration of the Distinguished Flying Cross. Even at the age of 12, I could tell that despite his modesty, Phil had been no ordinary pilot. And when Dad brought out a photo from Uncle Jack’s box, Phil immediately turned it over and pointed to his own handwriting on the back.

I wasn’t imaginative enough at the time to realise it, but this was just the first in what would become a series of connections that reached down through history, from that time to this. Ordinary items and moments, on the surface, that despite their very ordinariness somehow carried with them the weight of years, in a way more profound than you’d expect from the image on a simple photograph. Here was something that Phil himself had held, and had considered important enough to write on and send home, more than six decades previously. It was photograph of the inside of a briefing room, with Phil himself sitting in the middle of the crowd. Three other members of his – and Jack’s – crew sat in the back rows. The photo had been sent to my great grandfather, and then passed on down through the family to us, and on that summer’s day in 1997 it came back to Phil Smith.

After lunch, we went outside to the backyard, where the hill continued, covered in a verdant oasis of lush green ferns and mossy rocks. A photograph was taken to record the occasion.

There’s me, the gangly pre-teen, with my polo shirt tucked badly into my shorts and my arms hanging awkwardly at my sides. And there’s Phil, the wizened old man, wearing a pair of thongs with his shorts pulled up high and a spectacle case hanging from a piece of cord looped around his neck. He has white hair and gazes steadily into the lens, but there’s a certain melancholy about him.

As he was at the time, and as in that photograph, I suppose, he somehow still is, Phil was the final living link to Uncle Jack’s crew. He was the only person still alive who had, in several senses of the phrase, “been there”.

He alone knew what it was like to be a member of the crew of B for Baker as it flew over Lille.

He alone had known Uncle Jack while he was in the Air Force.

He alone had survived.

And somehow it didn’t matter that he couldn’t tell us much directly about Uncle Jack and that final flight to Lille. Just being in the presence of this bloke, this one person who was there, was to feel a connection to the time. To see his deep-set eyes under a slightly furrowed brow was to wonder what else he’d seen, how life had treated him.

There’s a story there, I thought.

And I wanted to find out about it.

After that first meeting with Phil Smith, I was hooked. What sort of war had he experienced, I wondered? What sort of war had Uncle Jack experienced? Why were they – two Australians – flying for the British Royal Air Force? What, for that matter, was Bomber Command, and what sorts of things did it do?

I began reading books voraciously. I wrote letters to Phil, and a couple of times a year we’d journey to Sydney to spend a few precious hours in his and Mollie’s company. The conversation was rarely about his wartime service, though. An intensely private and reserved man, as we came to discover, he preferred to dwell on current things like how we were going at school and how the rest of the family was. On one wonderful occasion he took me down into the depths of the garage under the house, a cluttered space jam-packed with old tools and bits of wood accumulated over a lifetime, all the bits of junk that ‘might be useful someday’, to share with me his collection of hand-made wooden propellers and electronics and old radios. Clearly Phil had a very technical and practical sort of mindset. But I could always detect a hint of gentle sadness in his eyes. Why had he, the captain of the aeroplane, survived, when the others did not? I suspect that question was never far away, though I can’t recall any direct mention of it. Nevertheless, we became friends. I kept writing him letters and I still have many of his replies.

But then, one day in 2003, we received a phone call from his son, telling us that Phil had died. He’d gone to bed as normal one night, and simply did not wake up the next morning. No fuss. A death befitting the quietly straightforward man he was. The final living link with the crew of B for Baker was no more.

This post is part of a series, publishing writing originally completed as part of my now-discontinued book project. Find an explanation of the series and an evolving table of contents here.

(c)2025 Adam Purcell