At the time, it was one of those moments that did not seem all that significant.

In mid 1993, I was a not-quite-ten-year-old boy who was interested in things like astronomy, science and space travel. I lived with my parents and two sisters in a big brick veneer house in a semi-rural village in the Southern Highlands region of New South Wales.

On this day, the sun was not yet above the horizon when, for once the first in the family to wake up, I opened my bedroom door and walked out to begin getting ready for school. Outside it was cold, the kind of cold where when it’s raining the freezing drizzle sticks to your face, and when it’s not raining, thick white frost covers the lawn and crunches underfoot. In the corner of the family room was our old wood-burning fireplace, which was lit around Easter each year and which we usually kept burning all the way until my mother’s birthday in October. It was normal in our household for Mum and Dad – who were both teachers – to leave important things at our respective places on the dining table, for us to find the next day. Normally they were boring but necessary things like lunch money or signed permission slips for school excursions, but this time I found something different. On that morning, by the glow of the fire’s smouldering embers, I first saw the box.

Of the old-fashioned foolscap size, the box was made out of rather tattered green and black cardboard. It might once have held overhead transparencies or some other tool of the teachers’ trade, but on this chilly morning, as I curiously opened it I found it now held very old photographs.

There was one of a man in uniform who, I thought, if I squinted a bit and looked at it from just the right angle, bore a startling resemblance to my dad.

There was one of several dark and indistinct figures, dramatically backlit, standing in front of a big aeroplane.

There were several photos that showed what looked like graves, marked with white crosses and covered in flowers.

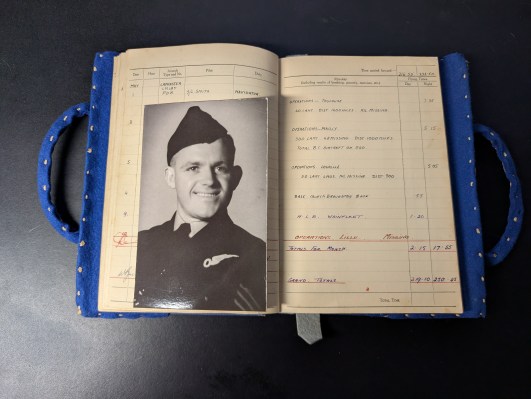

I found a small blue notebook in the box, too. Tucked into a hand-made cover of blue felt, the book was clearly old, its pages yellowed and brittle. It was filled with columns of numbers, times and unfamiliar place names, all inked in with a wide-nibbed fountain pen.

Nhill. Llandwrog. Lichfield.

Munich. Nuremberg. Berlin.

And on the final line, in red ink and different handwriting:

“OPERATIONS. Lille,” I read.

“MISSING.”

I had many questions for my father when he emerged from bed a short time later. Who was the man in the photograph? Why was he missing? And why did he look sort-of like Dad?

The man, it turned out, was “Uncle Jack”, and he had been a relative of ours. Dad told me that he had been in the Air Force , and that he’d been killed during the Second World War. The photos, and the logbook, were all that were left of him.

This post is part of a series, publishing writing originally completed as part of my now-discontinued book project. Find an explanation of the series and an evolving table of contents here.

(c) 2025 Adam Purcell