“[O]ur boys joined in the attack on the Marshalling Yards at LILLE” – 463 Squadron Operational Record Book, 10 May 1944

The concept of a marshalling yard in Lille has long formed part of my understanding of what happened to the man known in our family as ‘Uncle Jack’. It’s been part of Purcell family folklore, I suppose, for as long as I can remember: that the target of Jack’s Lancaster on that fateful night was a set of railway lines in northern France.

But which set of railway yards, exactly?

The thing about Lille, you see, is that it’s a pretty important railway junction. It’s now a key stop on the Eurostar cross-Channel tunnel route between Brussels and London, an hour from Paris on the TGV and about 40 minutes from Brussels. There’s also a significant local railway network. There are two key stations in the centre of the city; Lille-Flandres, which hosts local and regional trains and some high-speed TGVs, into which I arrived when I visited Lille in 2009, and Lille-Europe, serving the Eurostar cross-Channel trains and international TGV services, from which I departed three days later. While a lot of these train lines and services have been built since the Second World War, their slower fore-runners also ran through the city: Lille sat on the route from the ports of Calais to Berlin and on to Warsaw, for example, and one of the first railroads in France, the line between Lille and Paris, opened as early as 1846. Locomotive building and repair workshops were also located in the city.

It’s pretty clear, then, why the city’s railways were targeted as part of Bomber Command’s pre-invasion Transportation Plan. But which part of them, specifically, was the target on 10 May 1944?

In the International Bomber Command Centre’s superb Digital Archive I thought I found the answer: a bombing photograph from the night in question, which shows a distinctive set of marshalling yards amongst the smoke – just above the white bomb burst in the photo:

[

Extremely helpfully, the IBCC’s volunteers have geolocated this photograph over a modern-day map. I fired up Google Earth, bearing in mind that this is a modern-day image and a lot of this infrastructure wouldn’t have been present in 1944, and immediately found the relevant spot. The facility in the bombing photo is pretty clearly the Hellemmes workshops, circled in blue:

And it looks like the 50 Squadron crew who obtained the bombing photograph just missed the target – the centre of the photo, the point where the bombs themselves would have theoretically fallen, being plotted a little way south of the marshalling yards. In this view, which I’ve geolocated onto the Google Earth screenshot, the red ‘X’ marks the crosshairs:

If I remove the bombing photo overlay, you can see the red ‘X’ just above that little white building – not very far away from the marshalling yards at all:

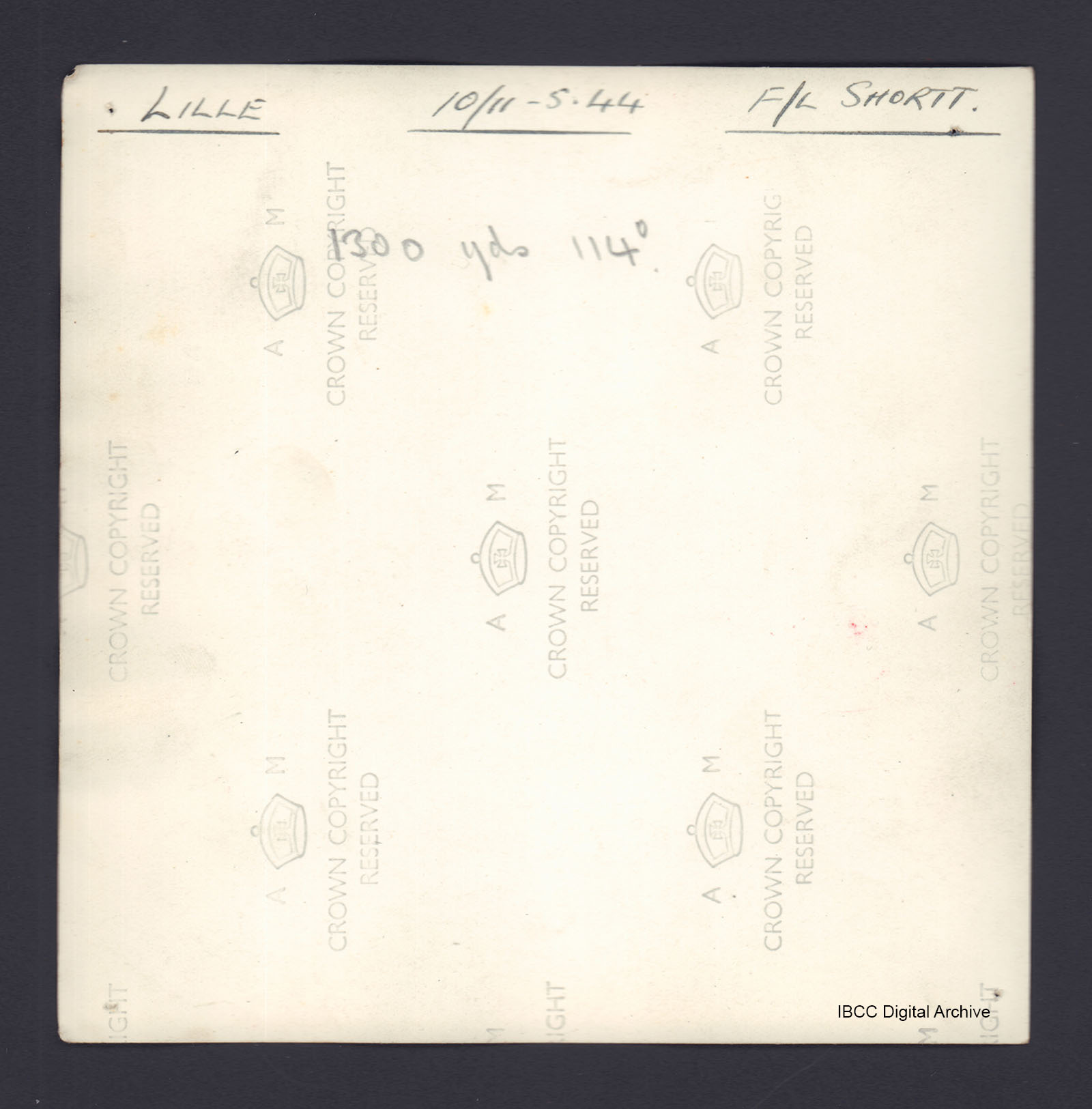

Or so I thought… until I saw the other side of the bombing photo, which has also been scanned in the IBCC’s Archive:

Hmm. “1300 yds 114°” – that looks to me to be a bearing and distance. I wonder if it’s a location referencing the actual aiming point, or in other words, how far away from it this crew’s bombs landed?

If 114° is the bearing of the photo from the aiming point, as I suspect, its reciprocal (114 + 180 = 294) is the bearing of the photo to the aiming point. So here’s a Google Earth ‘ruler’ showing where that point is. The bottom right of the yellow line is located on the position of the red ‘X’ in the earlier screenshot. If I’m right, the other end of it shows where the actual aiming point was:

Looking promising – that’s clearly one of the other marshalling yards. But can I find any other evidence to corroborate this theory?

I wouldn’t be writing about it if I couldn’t. In the Night Raid Report[1] from this night’s operation, there’s a description of damage as shown by later photo-reconnaissance:

A great concentration of bombs fell on and around the railways and sidings 200yds S.W. of the steel and engineering works of the Fives Lille company. 2 locomotive sheds and a repair shop were destroyed, together with numerous smaller buildings, and many hits were scored on lines and rolling stock. The Fives Lille factory and several other industries were damaged.

Where is or was the Lille-Fives company? It’s that white-roofed industrial area to the right – east – of the marshalling yard in the following screenshot. You might just be able to see the label above it that says ‘Fives Cail’; this is a new redevelopment project that aims to turn the old factories of the ‘Lille-Fives Company’, which later became known as ‘Fives-Lille-Cail’ and, now, simply ‘Fives’, into an urban project with housing, public areas and creative industries. But it’s where the Lille-Fives company was located during the Second World War, and its edge is clearly 200 yards north-east of the same marshalling yard identified by my yellow line earlier. In other words, the marshalling yard is 200 miles south-west of the factory, as noted by the Night Raid Report:

So it looks to me like the marshalling yards near Fives were the actual target for the bombers on the night of 10 May 1944. While the bombing was mostly accurate, some landed closer to the railway yards and workshops south of Hellemmes – and all of the six bombers that crashed within two miles of the target area, including B for Baker, fell east of the aiming point. That, however, is a story for another day.

Screenshots from Google Earth. IBCC material used under the CC BY-NC 4.0 Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Creative Commons licence. Analysis, additional geolocation and text © 2021 Adam Purcell

[1] The National Archives of the UK (TNA): Public Record Office (PRO), AIR 14/3411, B.C. (O.R.S.) Final Reports on operations, Night Raids Nos. 416-620, September 1943 to May 1944, vol. 4: Night Raid Report No. 602