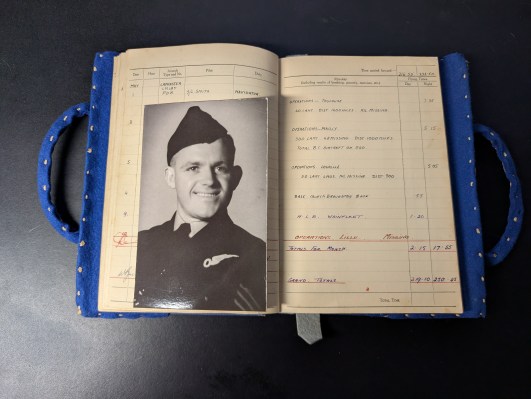

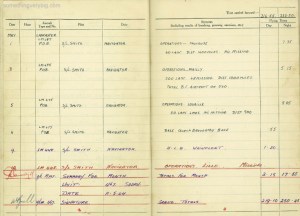

The first place I went in my journey to follow Jack Purcell was less a place and more an experience. It traced its beginnings to something in Jack’s logbook that I thought was pretty special. It took up fully one-third of an otherwise blank page, stamped in slightly smudged, dirty purple ink.

CERTIFIED THAT I UNDERSTAND THE PETROL, OIL AND IGNITION SYSTEMS OF THE TIGER MOTH,

it read,

…AND THAT I HAVE BEEN INSTRUCTED IN PROPELLOR SWINGING IN ACCORDANCE WITH FLYING STANDING ORDERS.

Then there was a line for the date – 23 March 1943 – and next to it, Jack’s signature, in uncertain running writing, inked in with a wide-nibbed fountain pen.

In light of what comes later, the story that the stamp told wasn’t the most dramatic or tragic or emotional one in the logbook. It was just a straightforward record of the fact that Jack was once qualified to swing the propeller – yes, the stamp spelt it differently – on a Tiger Moth. But for me, this simple stamp was one of the most significant parts of Jack’s logbook. And it was all because of where it led me.

Three weeks after I finished high school, many years ago, I was at Wollongong Airport, south of Sydney. It was a Thursday morning, a light southerly breeze blowing straight down the runway, and I was sitting in the left-hand seat of a little Cessna 152 training aeroplane. I looked over the top of the instrument panel, through the bug-splattered Perspex of the windscreen. Looked past the spinning disc of the propeller. Along the dashed white line marking the centre of the runway. To my right, for the first time ever, was an empty seat. My instructor Marty, only a few years older than me and later to fly big jets with Qantas, had just unbuckled his seatbelt, slipped out and closed the door and walked around the back of the aeroplane, waggling the elevators as he passed. The control yoke correspondingly bucked forward and aft in my hand in encouragement. I was a few months past eighteen years of age, and I was about to fly an aeroplane all by myself.

It was, I discovered, true what they said about your first solo. Without the weight of your instructor the aeroplane really did leap into the air. And you really were so busy in those first few moments that it was not until you climbed to height and turned to fly the circuit back to the top of the runway that you settled down enough to look at the empty seat next to you, and savoured what it meant. And then, after allowing yourself a brief moment of exhilaration, you got right back to business, working through the mental checklists you’d been taught as you slowed the aeroplane and turned to start the gradual descent back to the runway. A tiny float, maybe a gentle bounce, and then with a thump you were on the ground again.

Afterwards, back at the flying school, I proudly wrote into my logbook my first six minutes of solo time. Then I watched Marty as, with reverence, he placed a stamp on an ink pad and then pushed it firmly onto the page.

It was only a small stamp, but there it was, in slightly smudged, dirty purple ink:

I CONSIDER ADAM PURCELL COMPETENT TO FLY SOLO BY DAY IN C152 TYPE AEROPLANES.

It was only when I got home that afternoon that I realised the connection. I went to the cupboard where Jack’s logbook was stored, opened the tattered cardboard box and pulled out the little blue book. I turned straight to the page with the Tiger Moth stamp, then laid my own logbook open next to it. Now I’ve got a stamp in my own logbook, I thought.

This post is part of a series, publishing writing originally completed as part of my now-discontinued book project. Find an explanation of the series and an evolving table of contents here.

(c)2025 Adam Purcell