I’ve been trying to find more time recently to devote to my Bomber Command research – or, more specifically, to my Bomber Command writing. For several years the focus of that writing was this blog, but as those of you who’ve recently had to fight your way through the cobwebs and tumbleweeds to get here would know, there’s been not much of that over the last little while. I’ve had unrelated projects to work on which have taken much of my spare time in the last year or two in particular, but I’ve also been working on some Bomber Command-related projects too – including that book I’ve been threatening to write for a very, very long time.

One of the things about that is that, despite all that research over a couple of decades, there’s still stuff I don’t know. And as I’ve discovered, the best way for revealing exactly where the gaps are in my research is by trying to write about it. So occasionally, despite setting aside a day for “writing my book,” as I rather grandly call it, I have to hit the archives.

And that is exactly what happened yesterday.

For me, the concept of “the crew” and the surprisingly informal way in which they were formed is still one of the most fascinating things about Bomber Command. Putting equal numbers of each aircrew trade in a big room and telling them to sort themselves out was a remarkably effective strategy, and the generally accepted story is that, thus formed, crews stayed together through thick and thin, becoming as close as brothers.

The problem for me is that the evidence shows this is not what happened in Jack Purcell’s case. The pilot that he crewed up with at 27 Operational Training Unit (Lichfield) in June 1943 is recorded in his logbook as Flight Sergeant Saunders. But Jack had a new pilot by the end of his Heavy Conversion Unit course (F/Sgt J McComb) and, as we know, actually flew operations with yet another (S/Ldr Phil Smith). Somewhere along the way, belying if you like the “traditional” narrative, his crew changed.

Trying to write about this yesterday, I realised that I didn’t know what happened to Saunders. To fix that, I decided to go for a dig through my files. The first thing I needed to find was a full name. The 27 OTU Operational Record Book, fortuitously, lists the members of each course, along with the day they arrived and where they came from. Here I found my first clue. The only Saunders who appears in the lists for the period around when Jack was at Lichfield is AUS8687 Flight Sergeant A J Saunders, a pilot who arrived there on 1 July 1943.

Saunders’ service number is unusual: I would normally expect an Australian number to be six digits starting with a 4. Knowing that original documents are often hard to read or have errors, I checked what I had against the DVA WWII Nominal Roll. This revealed that the ORB was correct. Born in Charters Towers in 1917, Alexander James Saunders enlisted at Laverton in Victoria on 5 February 1940. Enlisting so early probably explains the unusual service number: perhaps the format had not yet been worked out at the time.

All I really wanted to know was where Saunders went after 27 OTU, so the list of postings in his Service Record at the National Archives of Australia would be sufficient for my purposes today. Unfortunately while that record exists, it hasn’t been digitised yet. It hasn’t even been examined for release. I could order the record online, but because there is a fee and a delay associated with that and all I really wanted was that list of postings, I decided to first check if there was any other way to find it.

What the hey, I thought. I’ve been lucky with Google before. I tried a simple search for his name and number… and found one little nugget of information that cracked the whole case open for me.

It’s hidden inside Volume IV of the so-called Official History of the RAAF during WWII[1], an account of an operation to an oil target at Wesseling on 21-22 June 1944:

A third Australian, Flight Lieutenant Saunders, also of 83 Squadron, was attacked six times by fighter aircraft before reaching Wesseling. (p.204)

In itself, this quote doesn’t show me much: there would have been more than one airman named Saunders. How do I know it’s the right one?

Happily for me, the author left a footnote, and that’s what made all the difference. “F-Lt AJ Saunders,” it says, “8687. 467 and 463 Squadrons, 83 Sqn RAF. Accountant, of Townsville, QLD”

There’s that strange service number again, which told me I’d definitely found the right man. And, more usefully, three squadrons are mentioned – two for which I happen to have full operational records.

I went to Nobby Blundell’s ‘Yellow Books’ which revealed that Alec Saunders and his crew had been posted to 467 Squadron on 31 October 1943. From here it was easy. Going to the original Operational Record Books, I discovered that Saunders flew twice as a second dickey before taking his own crew on one trip to Berlin on 23-24 November. A day later, they were all posted to the newly-formed 463 Squadron, with which they flew a further six operations. In early February 1944 they were posted to 83 Squadron, a Pathfinder unit.

Blundell records the names of the rest of Alec Saunders’ 467 Squadron crew:

- A J Saunders (Pilot)

- F D Redding (Flight Engineer)

- J S Falconer (Navigator)

- D D Govett (Bomb Aimer)

- T A Sheen (Wireless Operator)

- K G Tennent (Air Gunner)

- D M Robinson (Air Gunner)

I cross-checked these against course lists in the 27 OTU Operational Record Book, finding records for four of them (Saunders, Govett, Sheen and Robinson). It makes sense that flight engineer Redding and second gunner Tennent wouldn’t be at the OTU because the aircraft in use at OTUs did not require flight engineers and had no mid-upper turret, so the extra men didn’t join the crew until the Heavy Conversion Unit. But what about Falconer, the navigator?

It took me a moment to make the connection: at OTU, the navigator was Jack Purcell. He is included in the course lists, of course, but he wasn’t on Saunders’ crew by the time they got to the squadron. Where did he go? And where did Falconer come from?

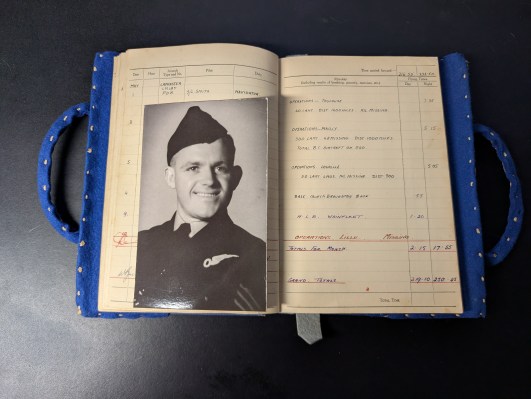

Amazingly enough, in my collection was another little gem of a piece of information which brought it all together. This is a page from Dale Johnston’s logbook, recording the names of his crewmates. Johnston was the wireless operator on the McComb crew – the bones of which became the crew of LM475 B for Baker:

See the third name? The one that’s been scratched out and replaced?

Sgt J S Falconer.

Falconer was Paddy McComb’s navigator right up to the end of Heavy Conversion Unit. Then he disappears, to be replaced by…

Jack Purcell.

Purcell and Falconer swapped crews.

I don’t know why.

But for whatever reason, at the end of October or the beginning of November 1943, just before their final flights at Heavy Conversion Unit, two crews swapped navigators.

Falconer went off with Alec Saunders and his crew and survived the war.

Jack Purcell went off with Paddy McComb and his crew – and didn’t.

Such, I suppose, are the fortunes of war.

© 2020 Adam Purcell

[1] Herington, John (1963) Australia in the War of 1939-1945. Series 3 – Air. Volume IV, Air Power over Europe 1944-45, Australian War Memorial, Canberra. Available from https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1417318